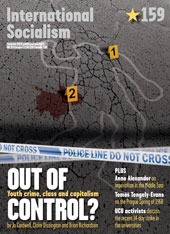

International Socialism: Out of Control? Youth Crime, Class and Capitalism 159

Summary

“What’s the danger in turning a blind eye? Your son might die”.1 That was the chilling headline of the “Saturday Interview” with Metropolitan Police Commissioner Cressida Dick in The Times on 31 March this year. Elsewhere in the article, Dick observed that “it is really shocking that you are 10 times more likely to be killed if you are a young black man than if you are not”.2 In the preceding fortnight ten people had been stabbed to death in the capital. In the following week a series of attacks brought that horrific reality home to the families and friends of a number of other young Londoners. These murders catapulted the issue of violent crime into the headlines across the media. By early April this year, more than 50 such deaths had occurred in the capital. It was calculated that if this rate were to continue, there would be 180 in London by the year’s end, the highest number since 2005. There can be few things more heartbreaking than the loss of a loved one in such tragic circumstances. There are those who draw a distinction between those such as 17 year old Tanesha Melbourne, one of those who died over the Easter period who, we were told, was an innocent victim who was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, with those whose social media posts suggest that they were heavily involved in violent and feuding gangs. But we should treat all these deaths as tragedies. Our hearts should go out to the families and friends of all the people who have been slain.